Max Winter, pioneer of social reportage, ventured where others dared not even look: to the fringes of society in the Habsburg Monarchy. Born in 1870 on the Hungarian side of “Kakania” and raised in Vienna, he focused his gaze on the dark sides of the metropolis and beyond. While turn-of-the-century Vienna is mainly remembered for being the golden heart of Kaiser kitsch, for its intellectual coffee house culture and Jugendstil, Winter brought a hidden flipside into the spotlight, revealing the blind spots of the urban moloch and its exploitative fundament: He gave the city’s untouchables and unsheltered a voice.

After discontinuing his university studies, he became a journalist in his early twenties. Victor Adler, founder of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party, brought him in to work on the “Arbeiter Zeitung” newspaper in 1895. There, Winter found a place he could write ground-breaking reportage pieces that had urgent political relevance. He was not afraid of being thrown into sordid prison cells while working incognito, nor did he shy away from precisely documenting the lives of those who lived in the sewers of the city as pariahs. In his participant observations, Winter let himself fall, with no safety net, into alien milieus and turned his research into a weapon – single-handedly exposing inhumane living and working conditions: be it in brickworks, ice houses or child labour factories. His fieldwork took him from Vienna to Bohemia, to the Trieste fish market and the slums of London.

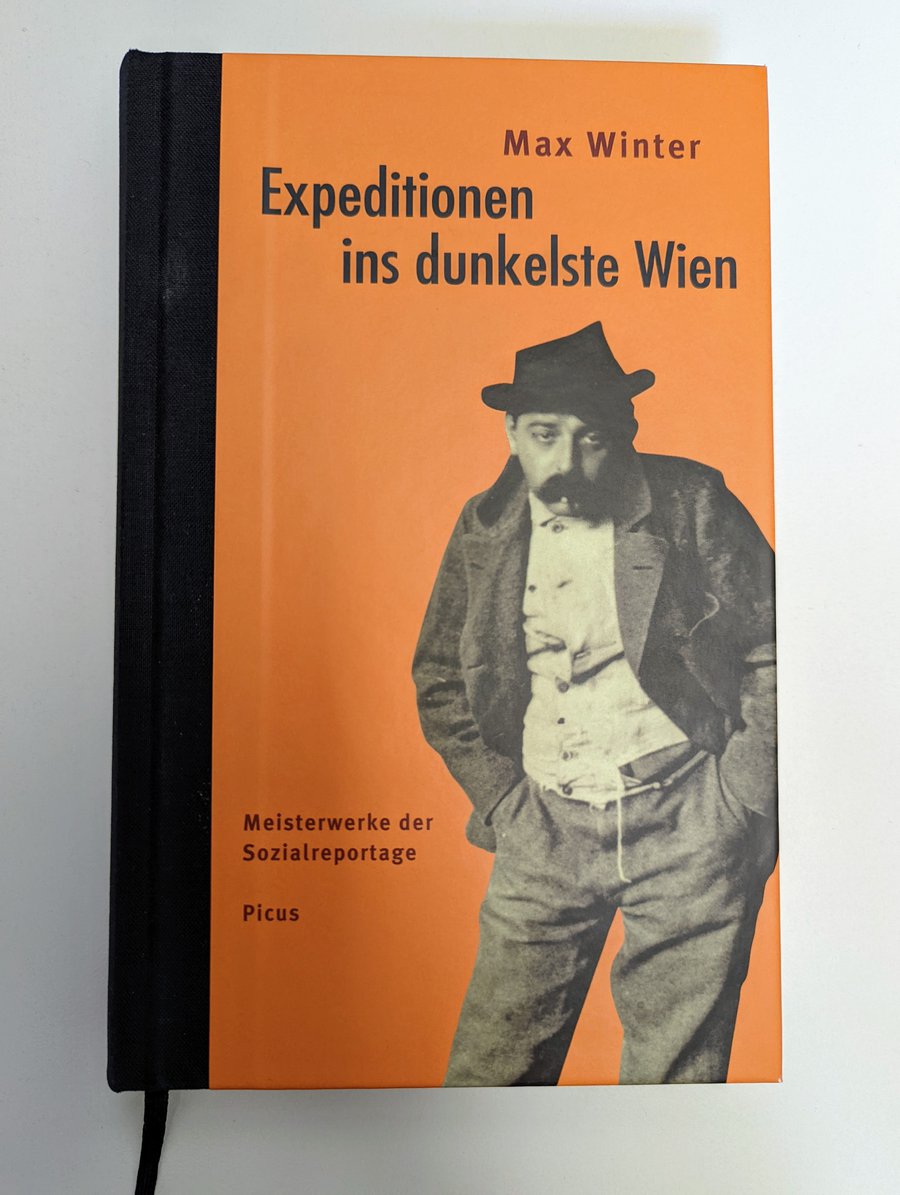

Winter’s texts never seem voyeuristic; he was committed to improving the lives of these social outcasts and brought to the surface what the majority actively ignored. Winter shocked with his simple depictions of the harsh realities of daily life that he underpinned with scientific facts and meticulous archival work. In the course of his career, Winter wrote about 1,500 reportages, and “Expeditionen ins dunkelste Wien” is a representative cross-section of his oeuvre. The anthology, edited by professor of journalism Hannes Haas, provides an excellent overview of the Max Winter universe, and includes a glossary of expressions that hail from the time and milieus that he documented.

But Winter was not only involved in the written word: He became a Social Democratic member of parliament and, after the First World War, vice mayor of Vienna. In 1934, he fled “Austrofascism” and died in poverty in Los Angeles three years later.

Today’s living and working conditions make Winter’s texts seem more relevant than ever. The fact that journalists like Günter Wallraff, and many others, followed in his footsteps decades later should not be dismissed as mere copying, but rather they are a reminder: The worlds that Winter reveals may look different in this day and age but, ultimately, they still serve to highlight the existence of the same merciless systems that he attested to all those years ago: Things can’t go on like this for much longer.

The work of Max Winter is a powerful and ageless indication that social conditions have been a mess for far too long. It’s time for a re-read.

Review by Clemens Marschall

This review was written for the ACF London's EXPLORE OUR LIBRARY initiative.