Virtual Exhibition: For the Child / Für das Kind – Stories of the Kindertransport

- Fri 28 May 2021

The ACF London is pleased to re-open with a very special exhibition featuring stories of the Kindertransport. We would like to ensure that this exhibition is available to everyone therefore we present this virtual version for those unable to visit the ACF at this time.

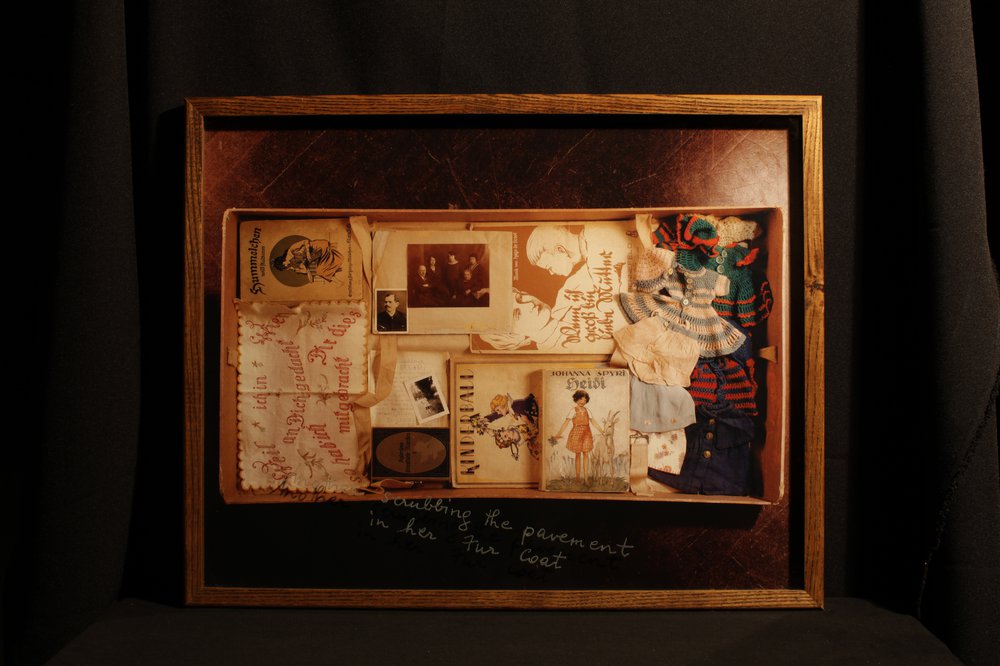

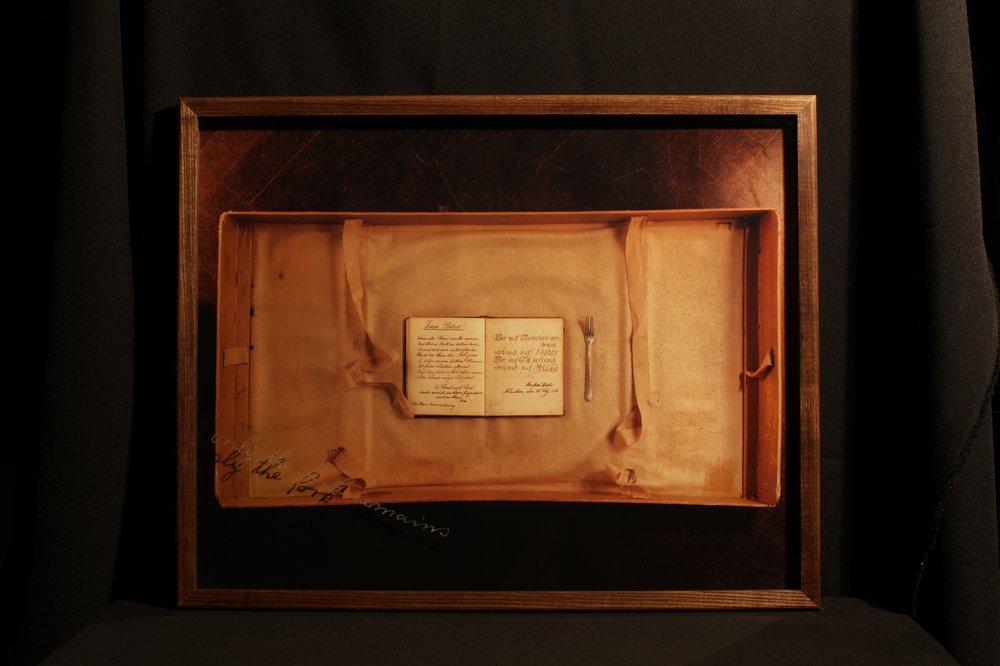

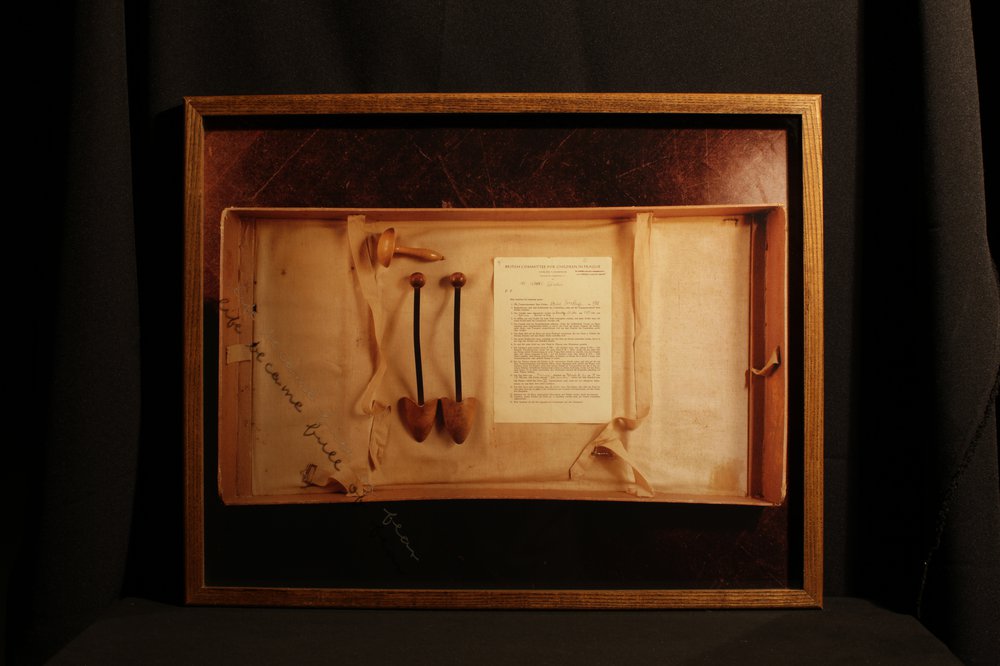

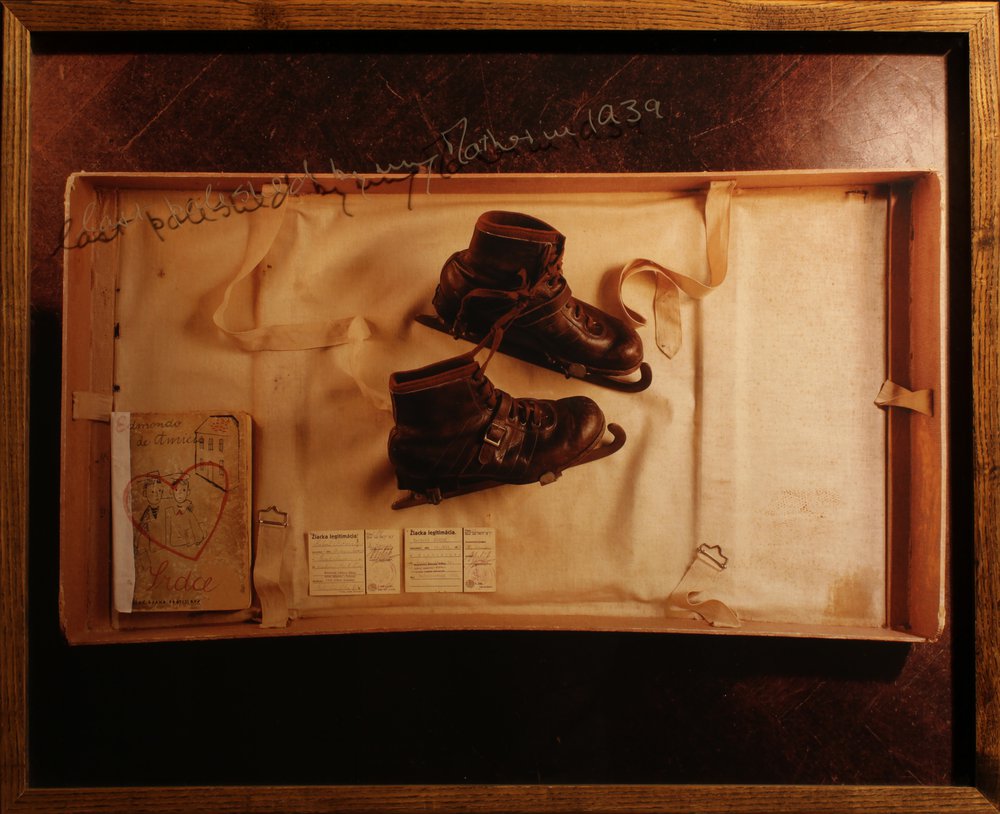

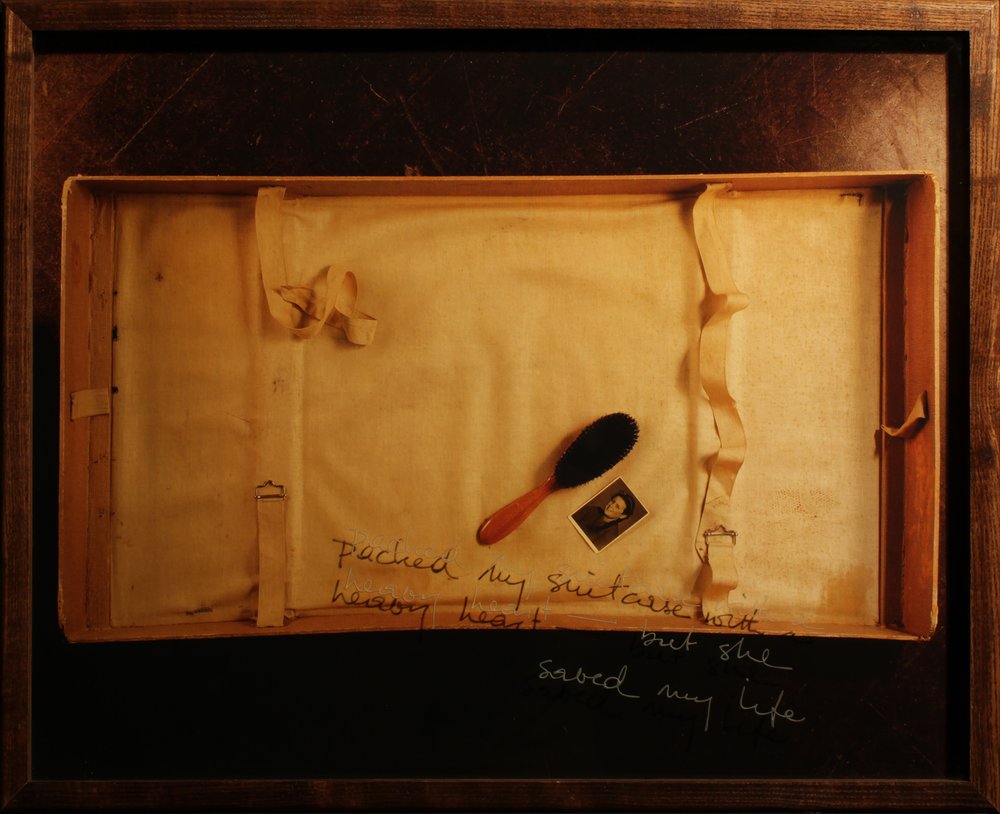

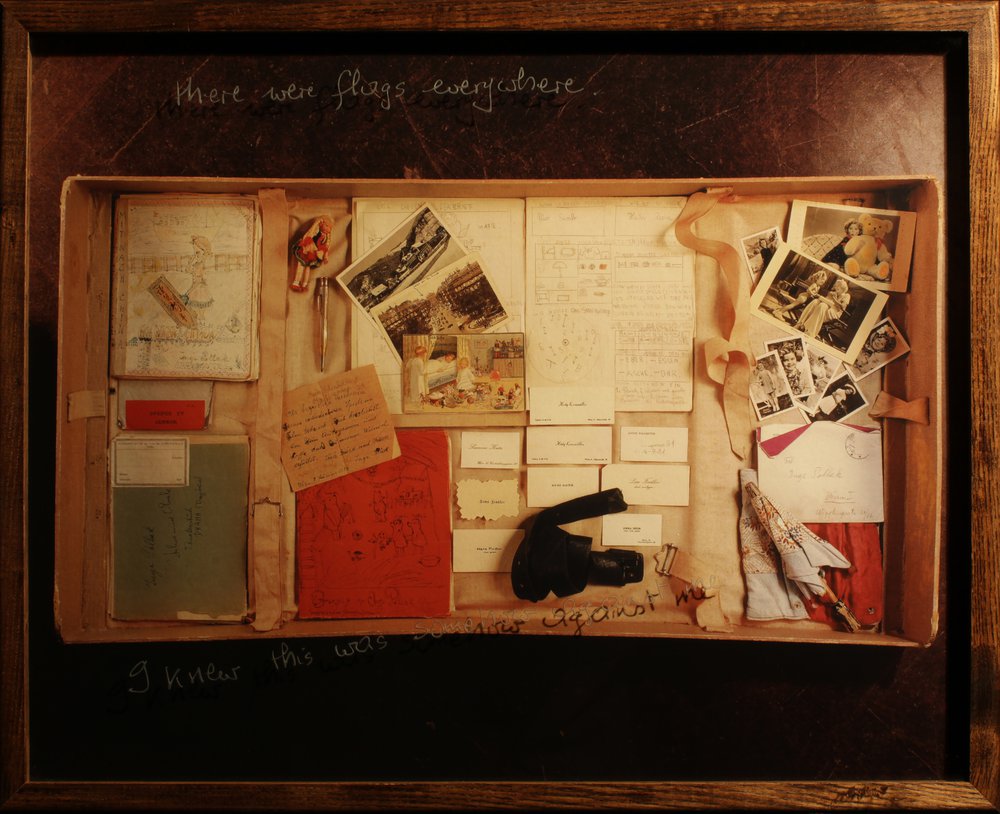

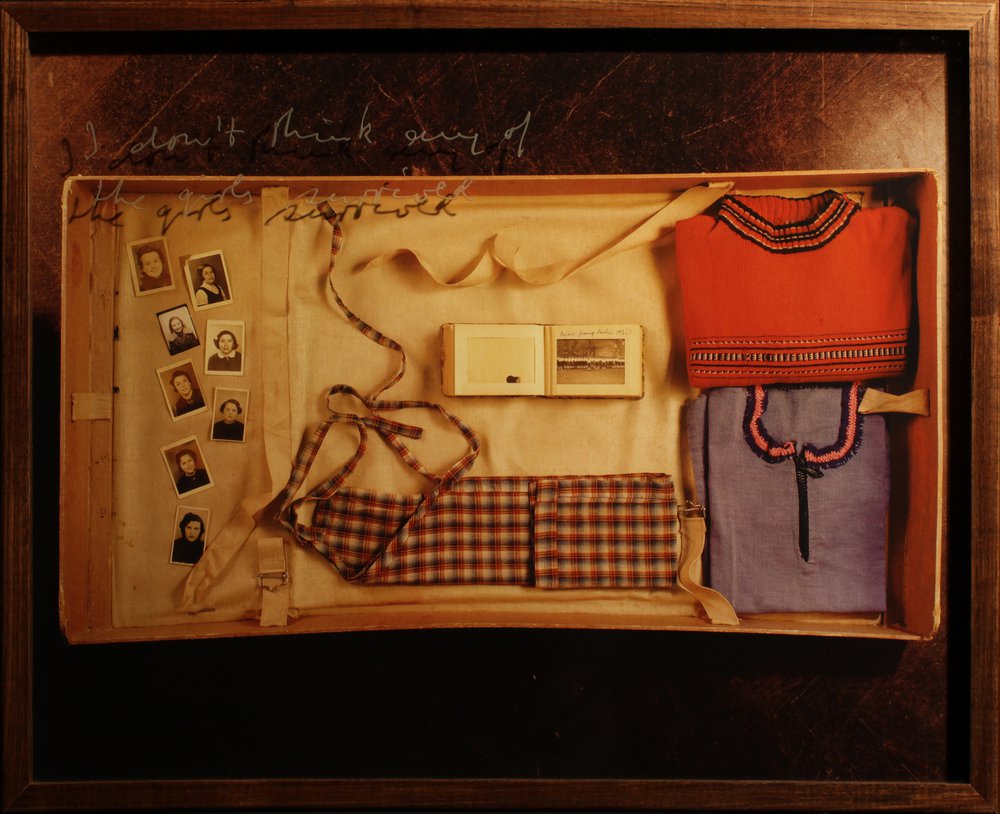

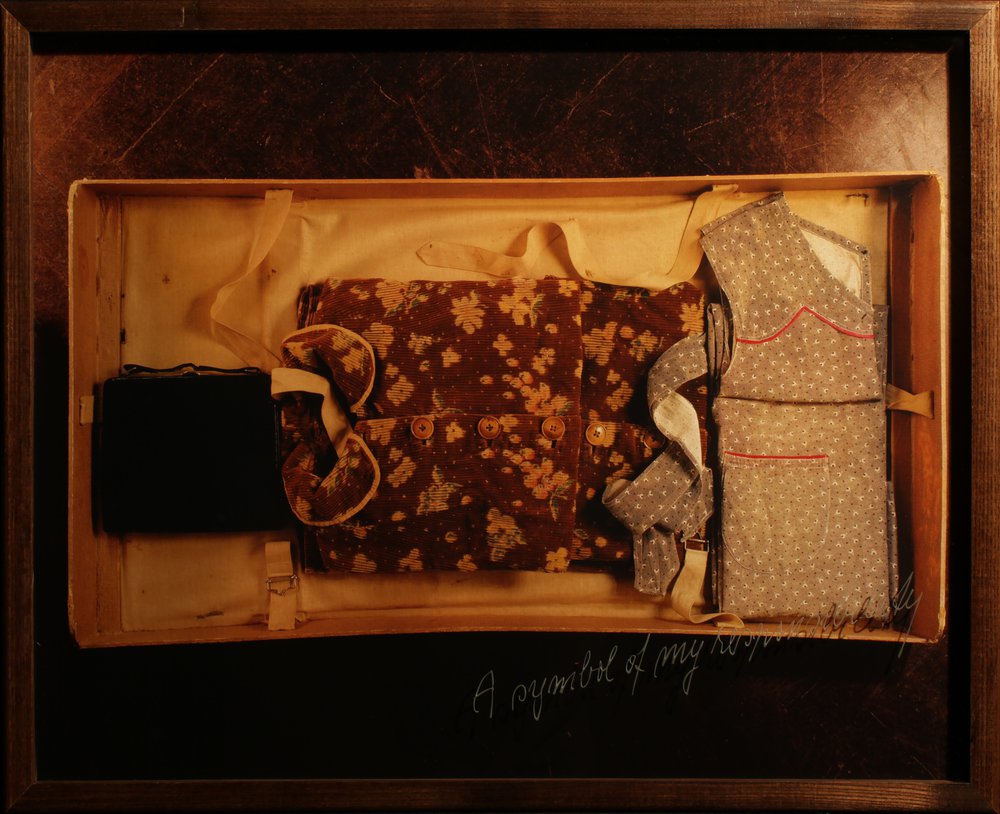

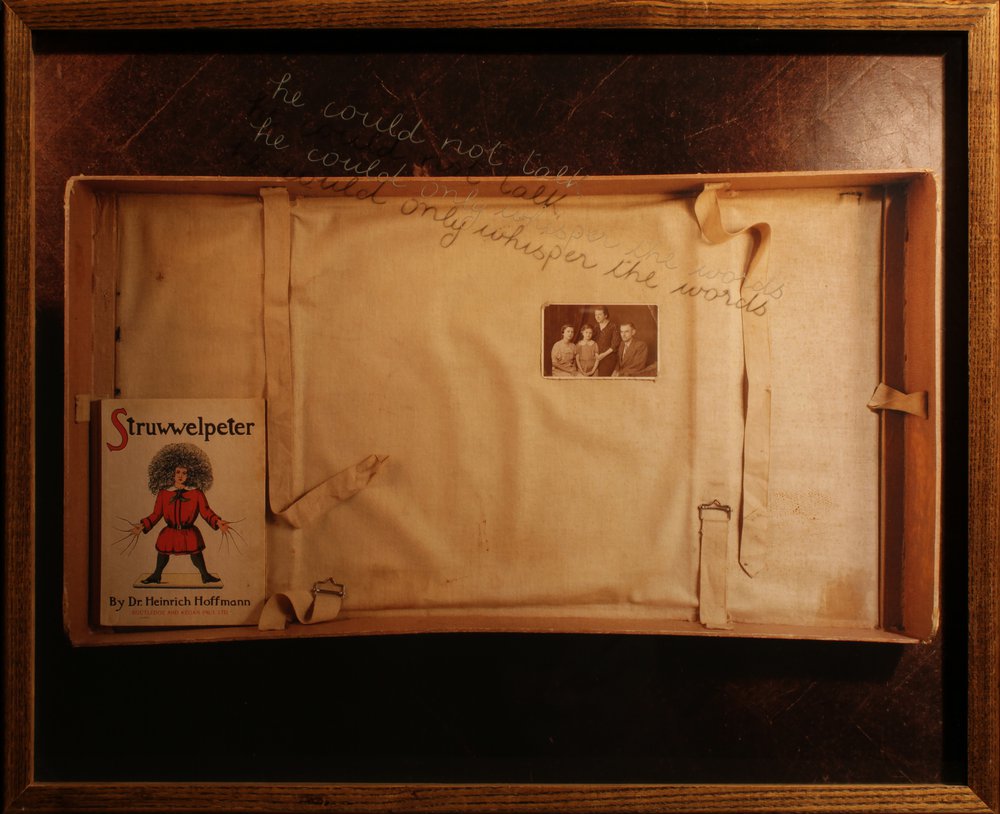

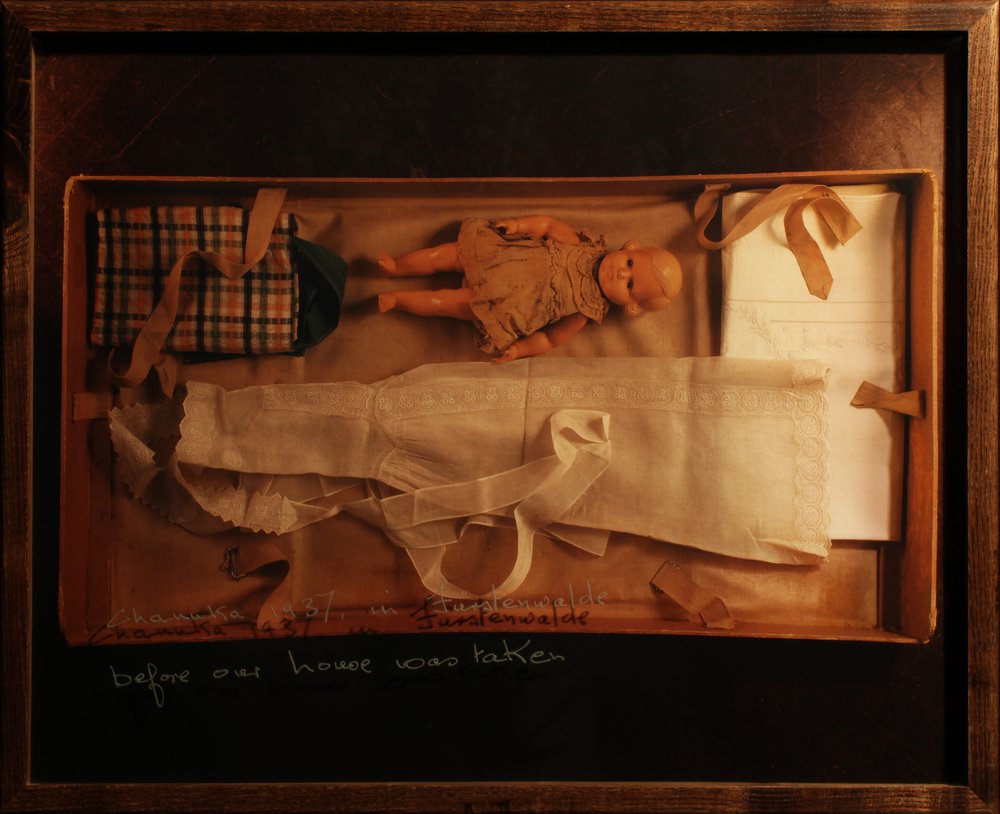

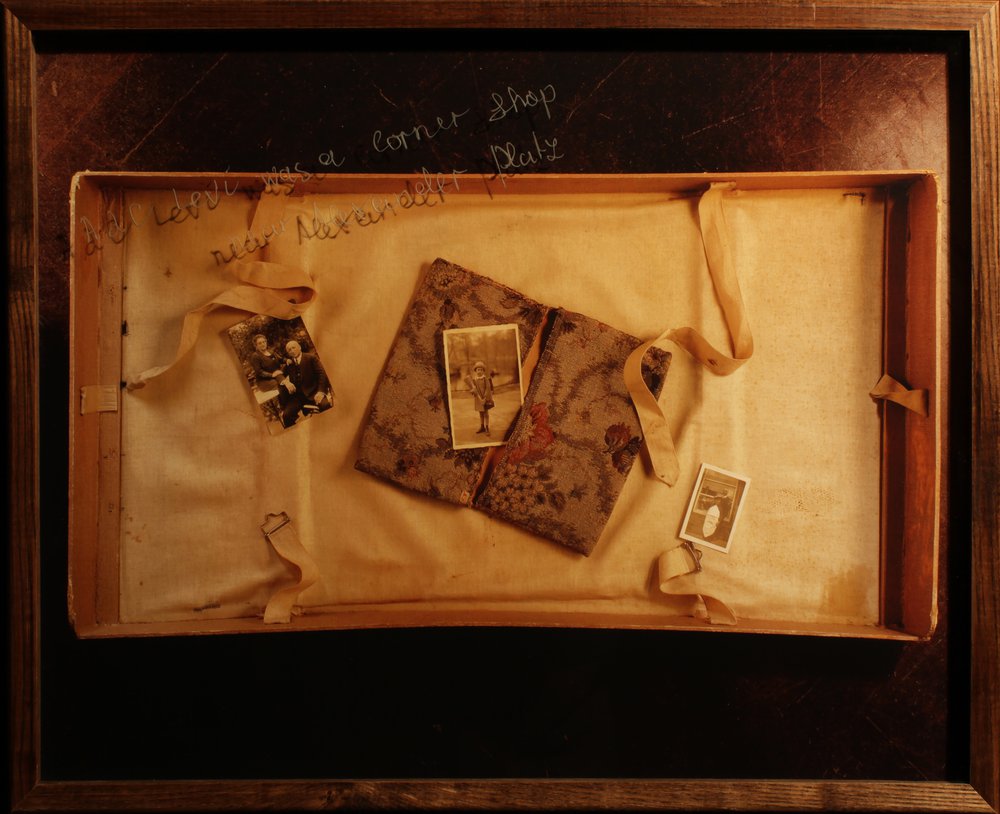

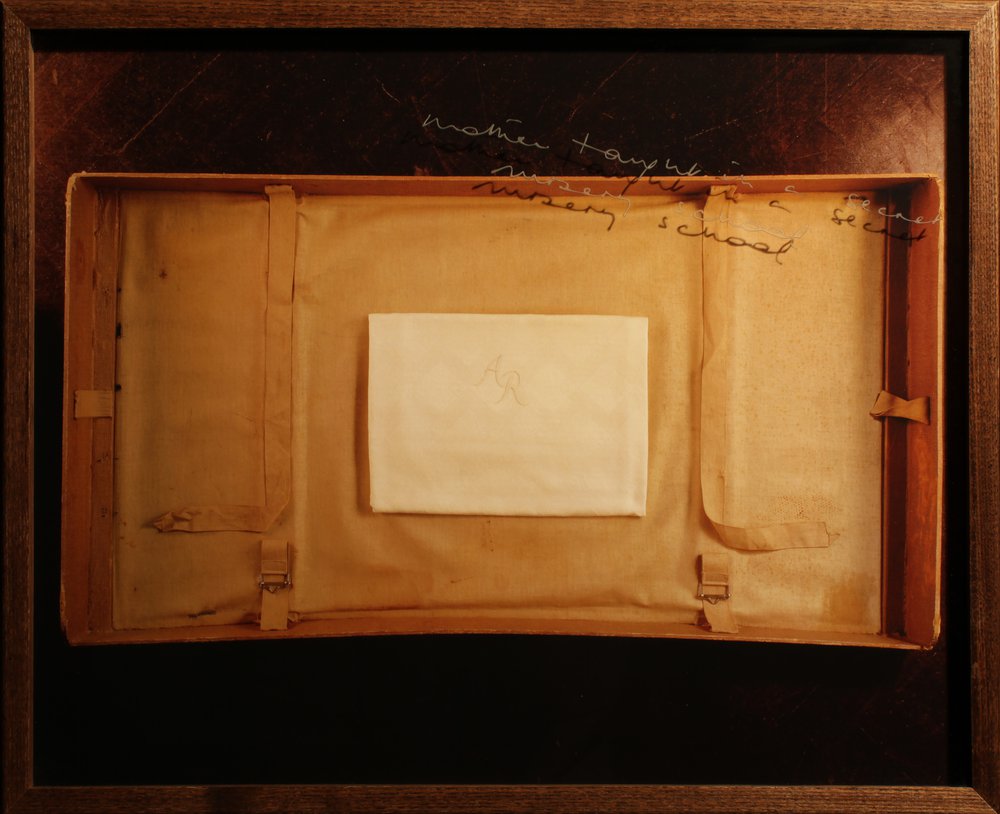

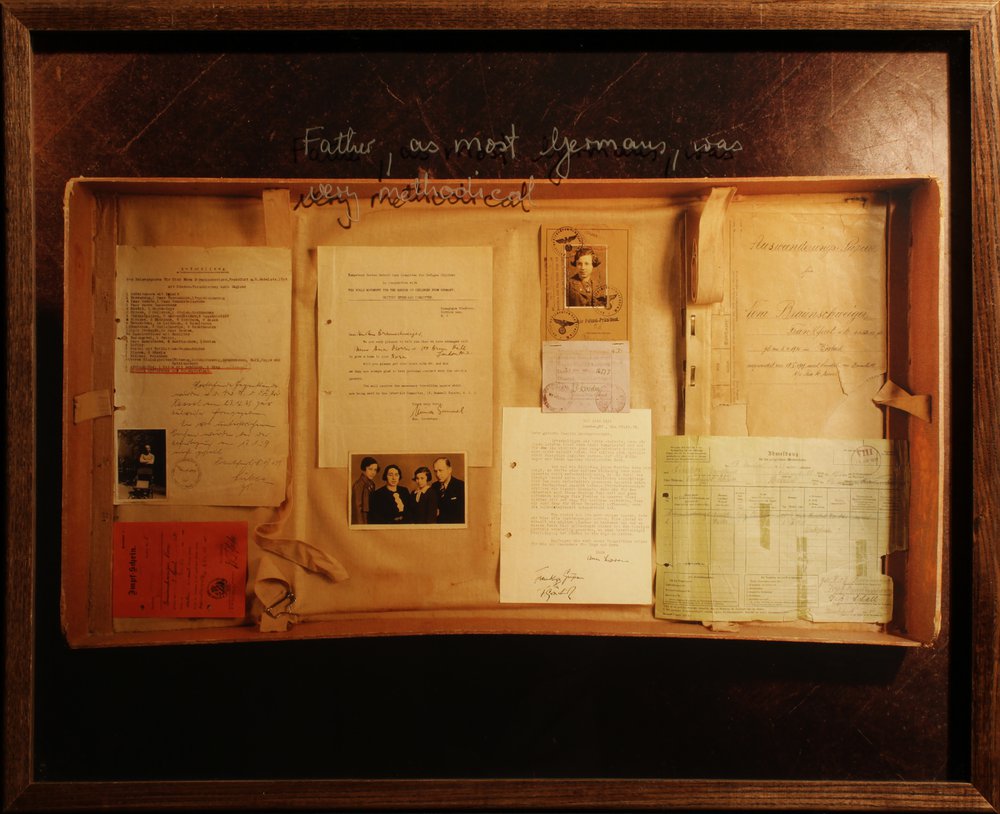

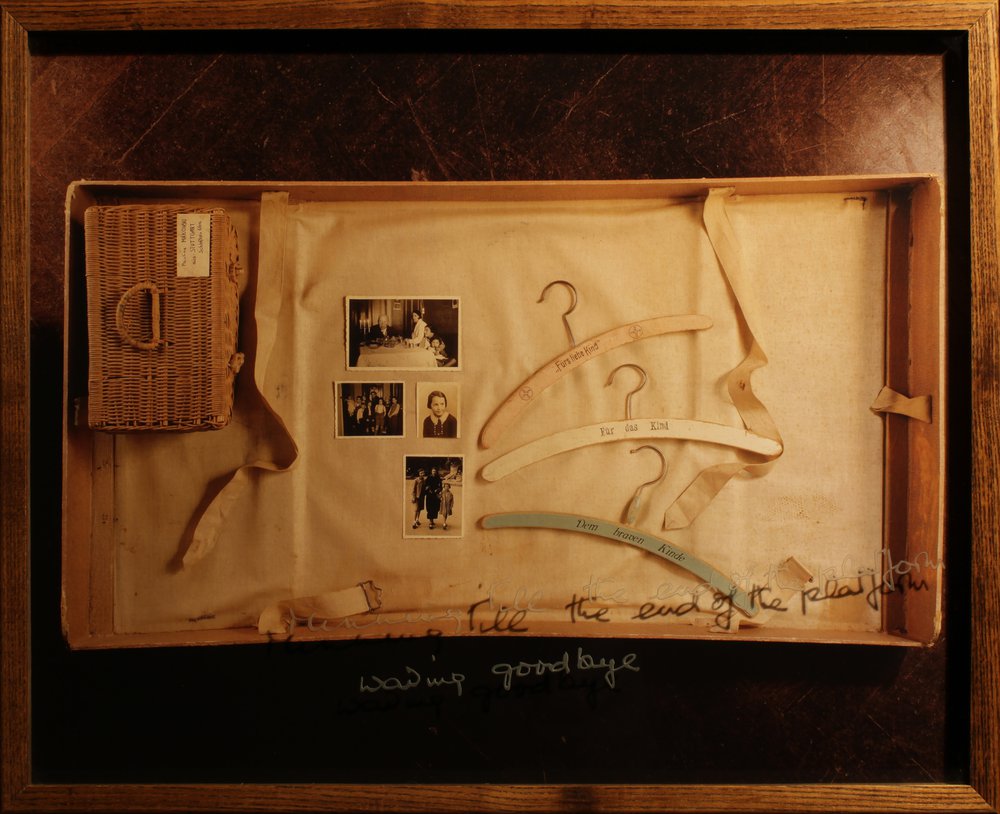

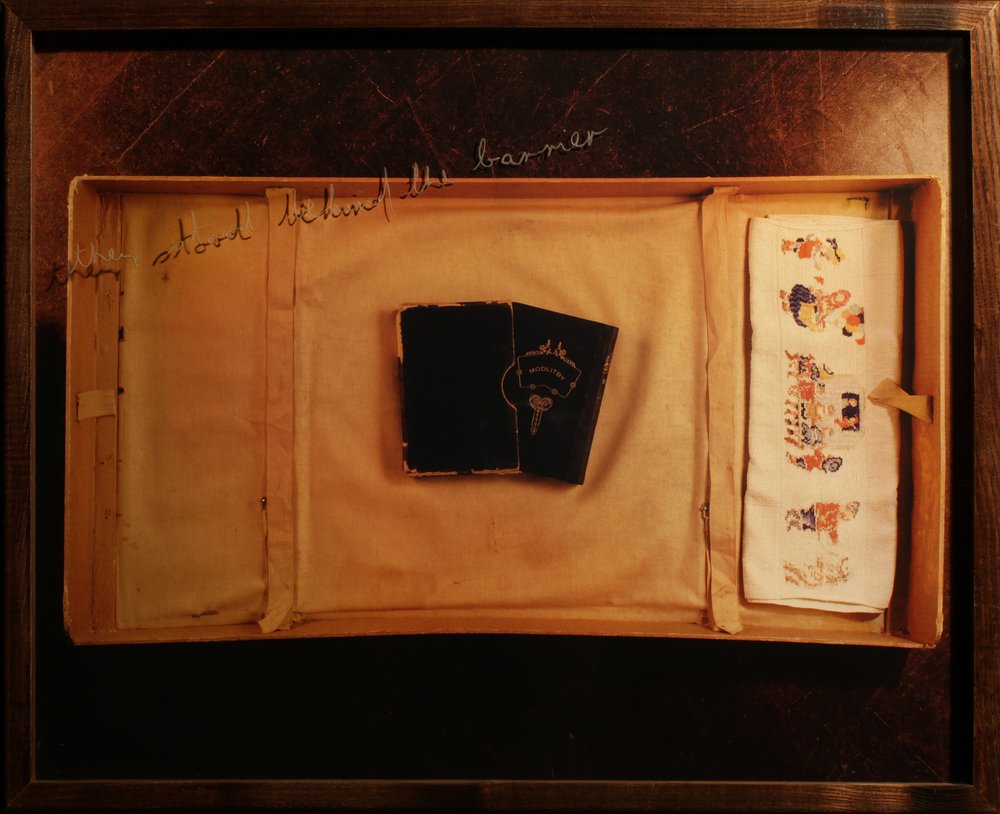

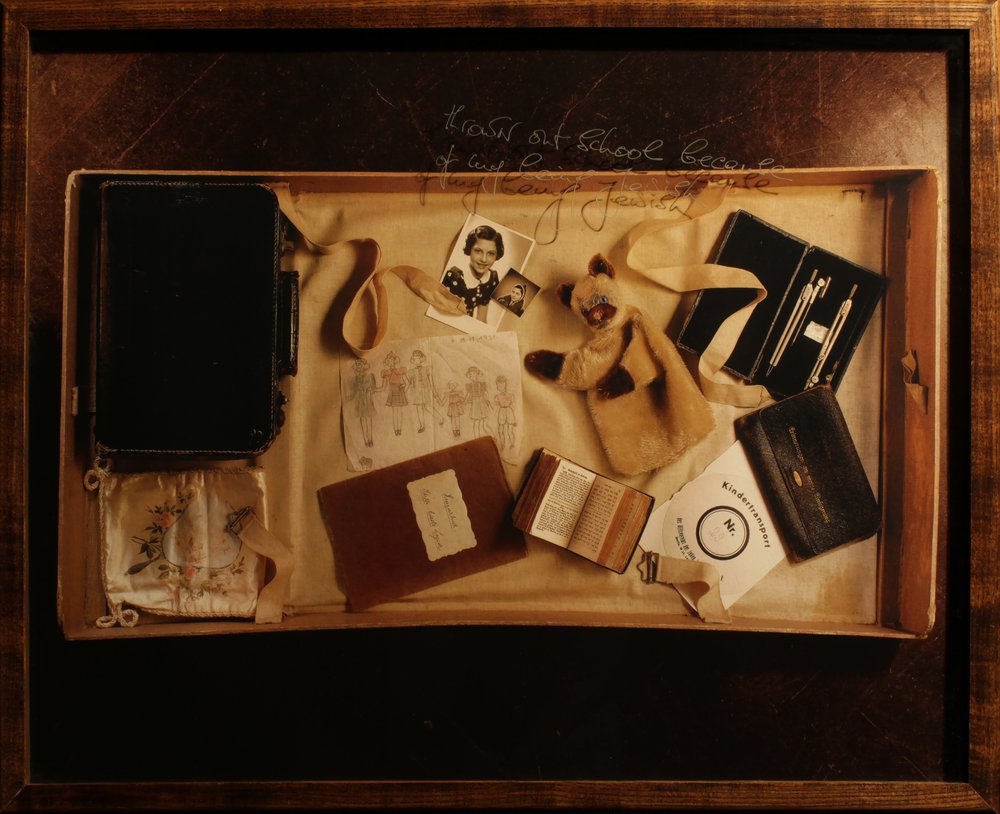

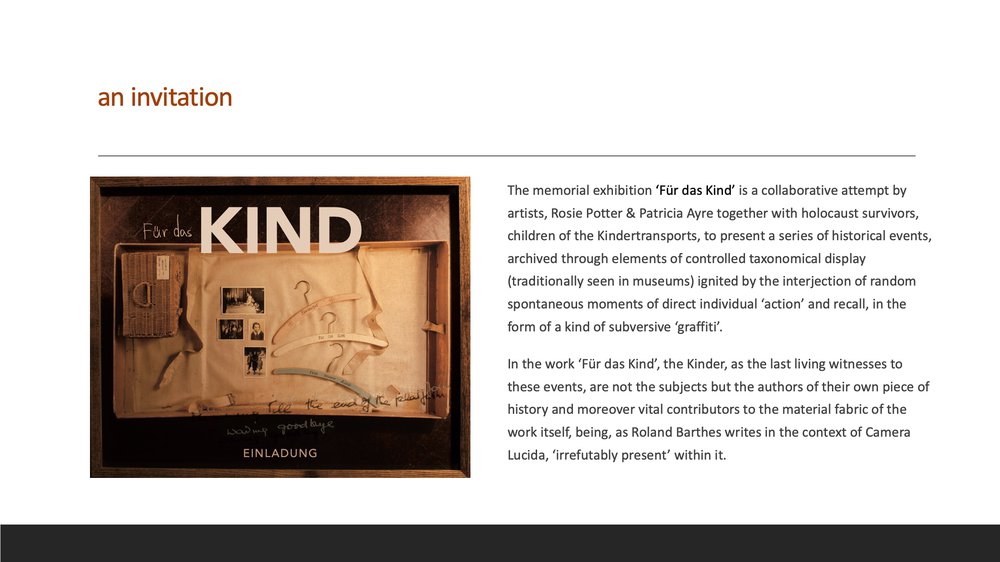

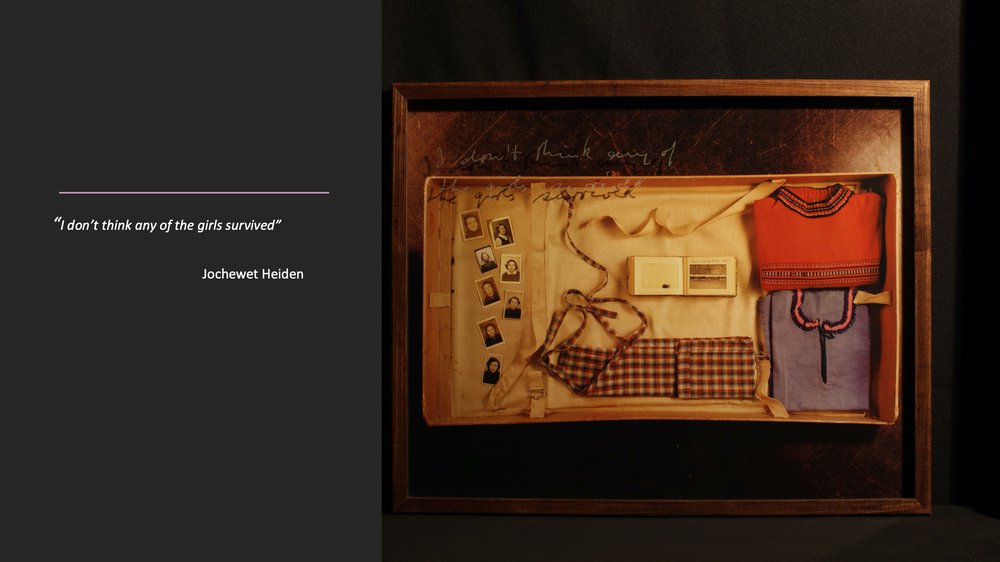

The photography project For the Child/ Für das Kind by artists Rosie Potter and Patricia Ayre presents and revisits the dramatic history of the Kindertransport. Potter and Ayre asked survivors to share the personal belongings that accompanied them as children on the Kindertransport. Very often these objects were the last physical contact the children had with their parents. The photographs presented here convey the deep emotions and trauma of the separation but also the hope of survival and start of a new future.

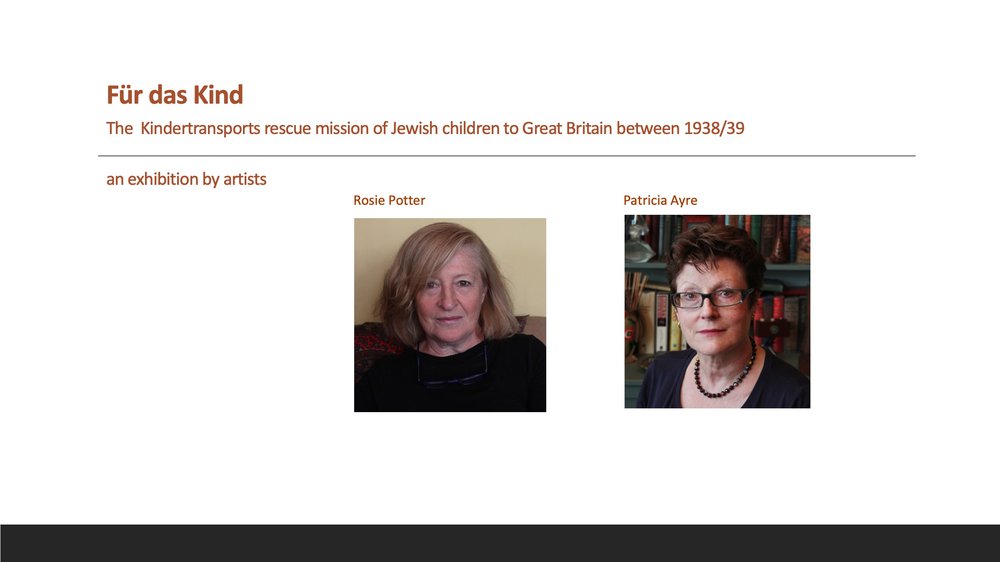

Rosie Potter and Patricia Ayre: Artists

The photographic works presented here were created by Rosie Potter and Patricia Ayre from 2000 – 2003, in response to a request for a memorial that was raised by surviving Kinder at a meeting of the ‘Reunion of Kindertransports’ held in London.

This request generated a two-part response by the artists Potter & Ayre and sculptor Flor Kent. Kent went on to produce a bronze sculpture of a child, cast directly from descendants of the original Kinder, placed at Liverpool Street Station, the main arrival point of the Kindertransports, as well as a second sculpture of a boy sitting on a piece of luggage at Vienna’s Westbahnhof (2008). Potter and Ayre created a memorial exhibition which would be able to travel to the ‘Kinder’s’ countries of origin, where for so many years the Jewish absence due to the atrocities of the Nazi regime had left such a deep cultural void.

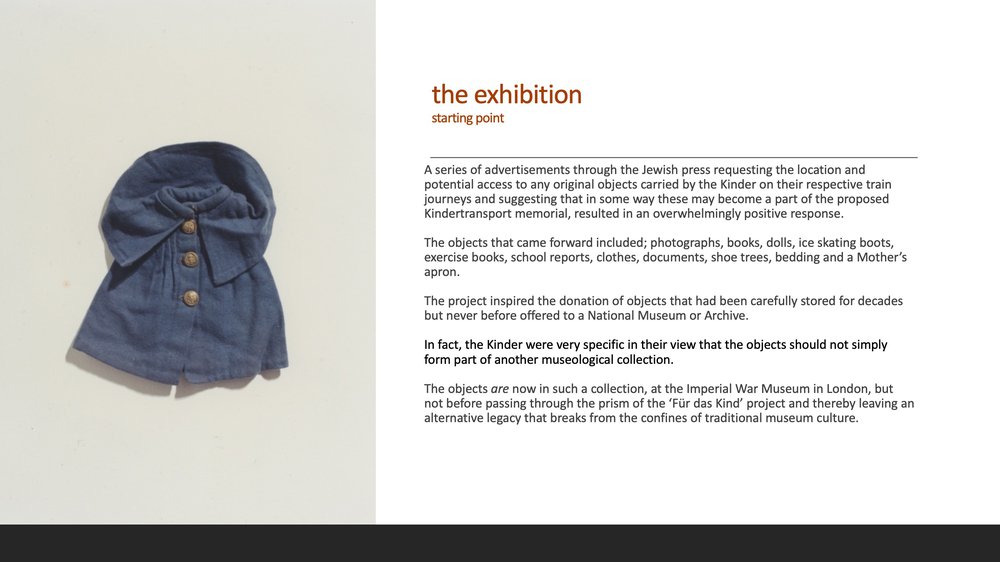

The original aim of the FÜR DAS KIND project was to re-present this little-known piece of history to new audiences and directly connect the Kinder ontemporaneously to their own history through physical and authentic elements of witness and survival embedded within the work itself. A series of advertisements in the Jewish press requesting original objects carried by the ‘Kinder’ on their respective train journeys, and suggesting that these might become an actual part of the memorial, resulted in an overwhelming response.

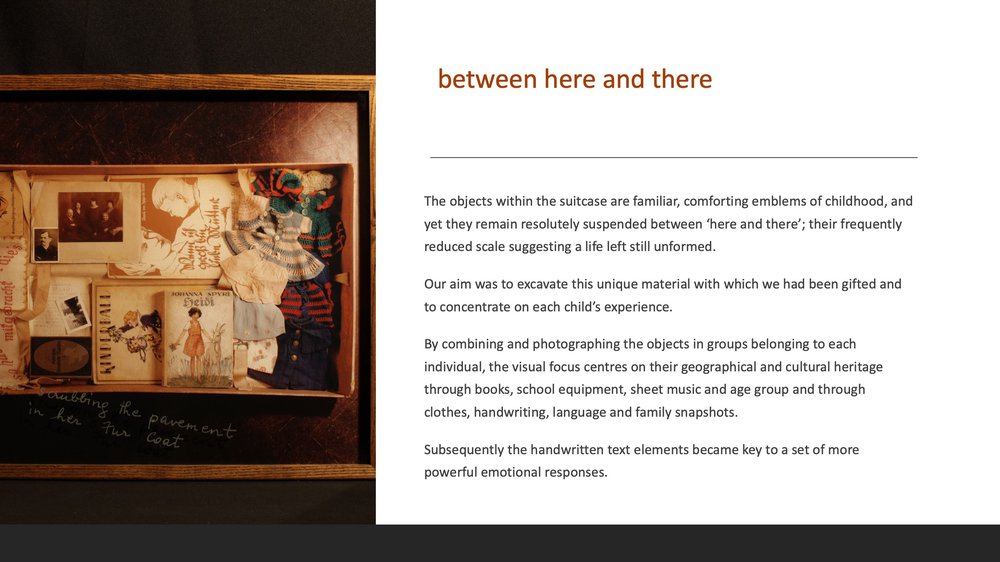

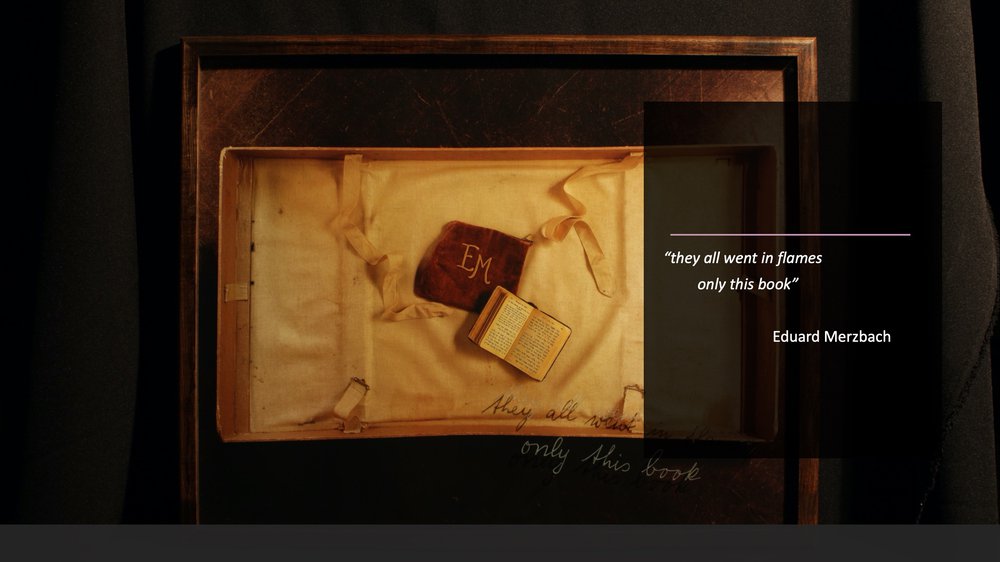

The objects that arrived included photographs, books, dolls, ice skating boots, exercise books, school reports, clothes, documents, shoehorns, bedding and a mother’s apron. The project inspired the donation of objects that had never before been off ered to a National Museum or Archive.

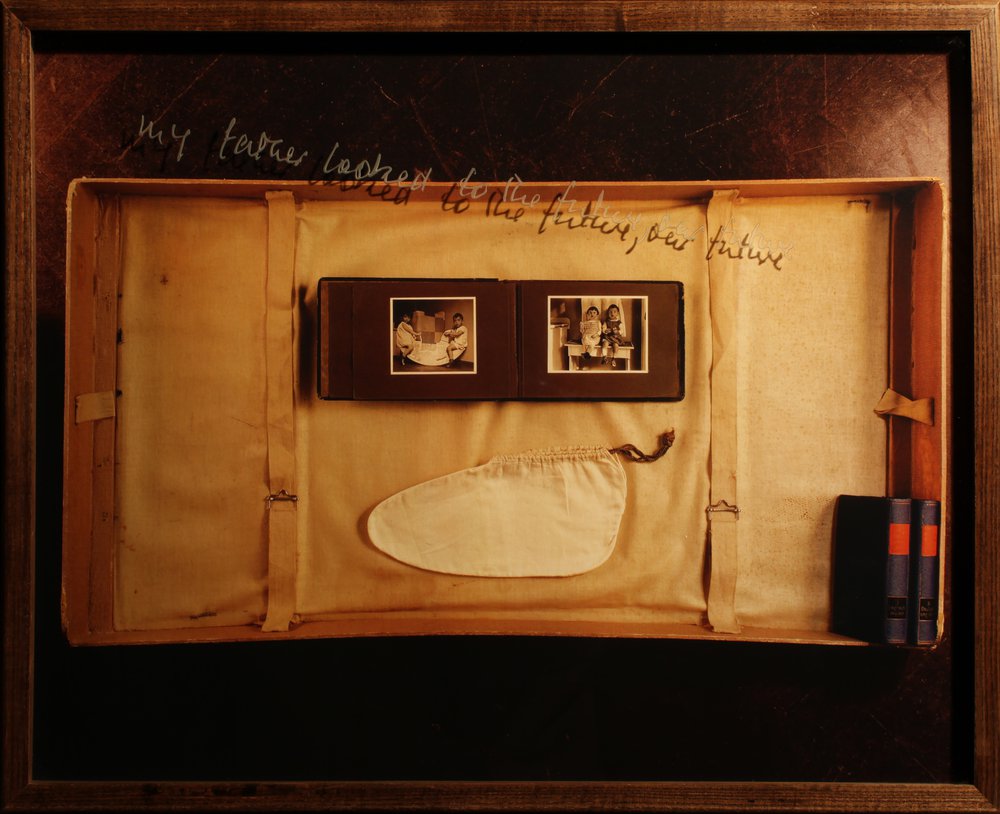

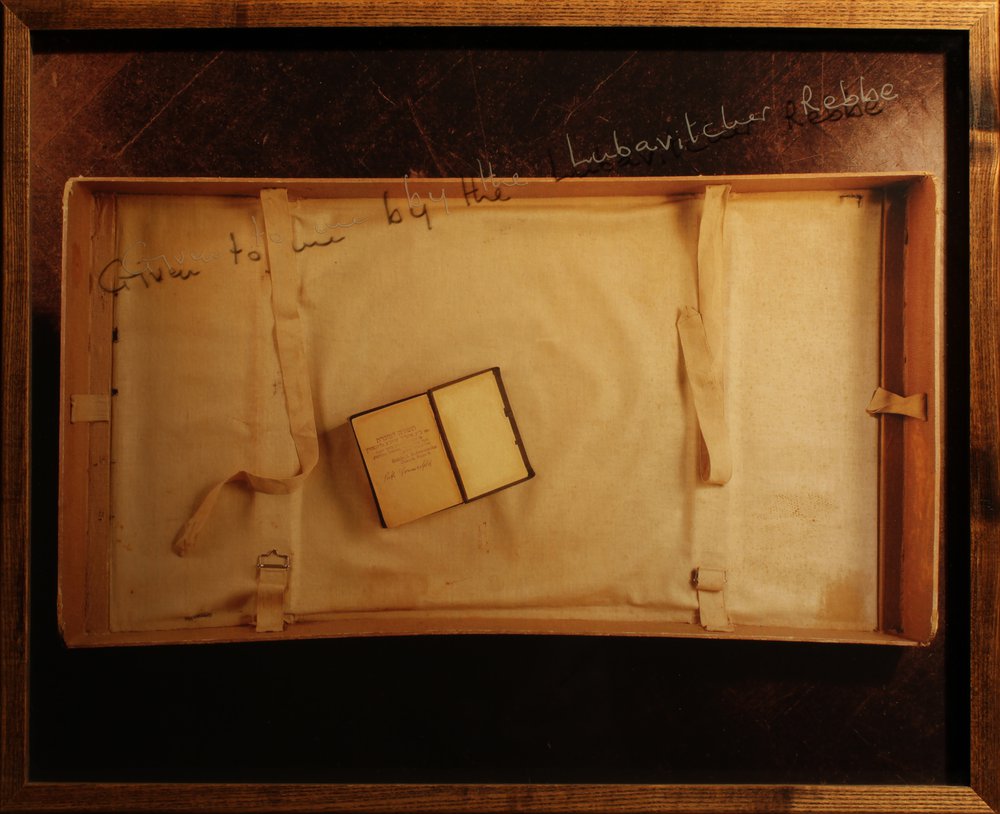

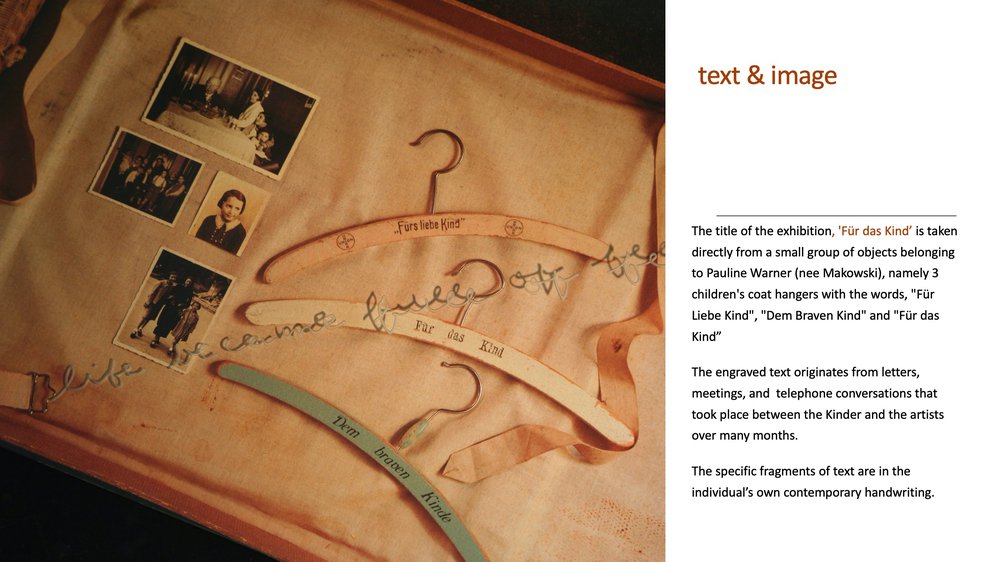

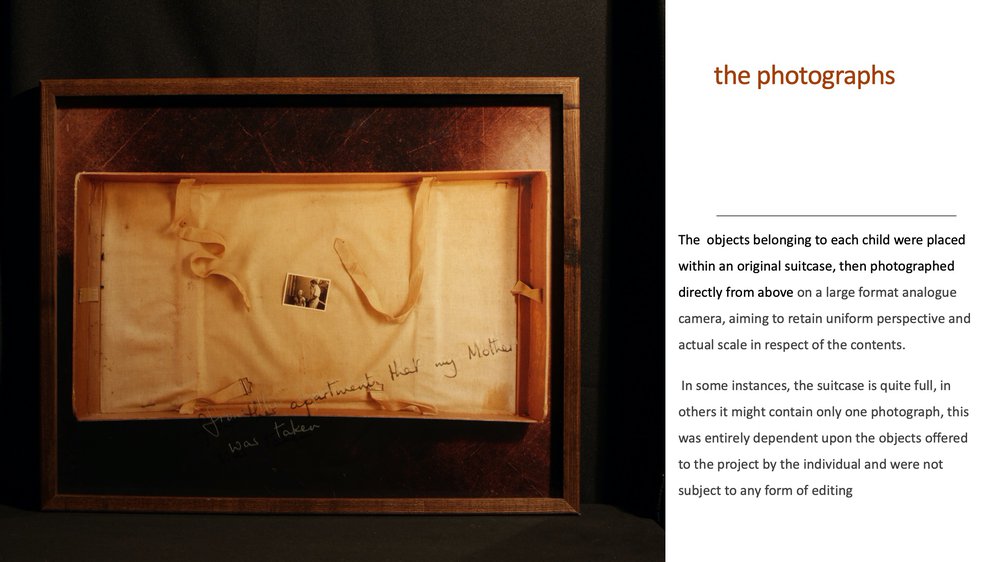

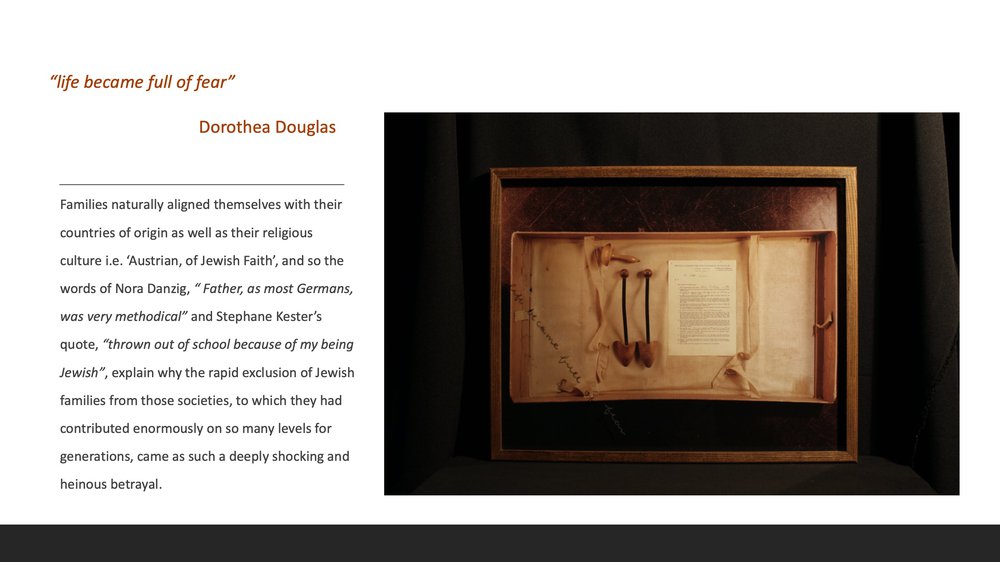

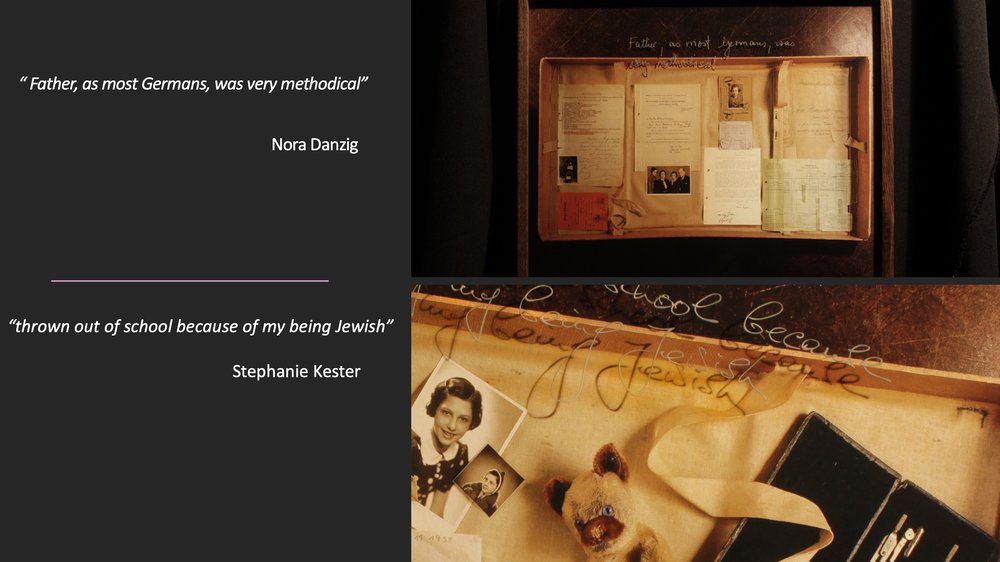

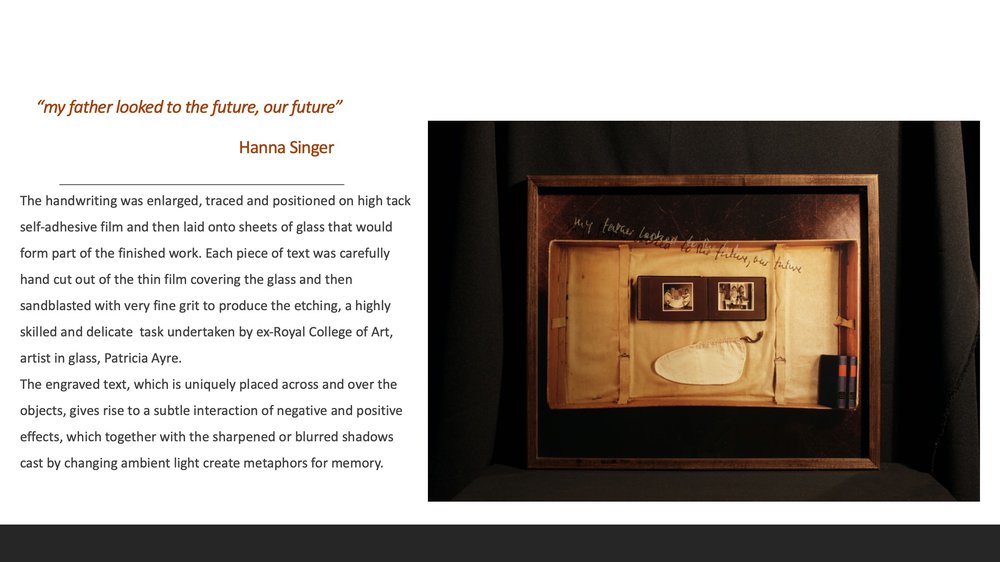

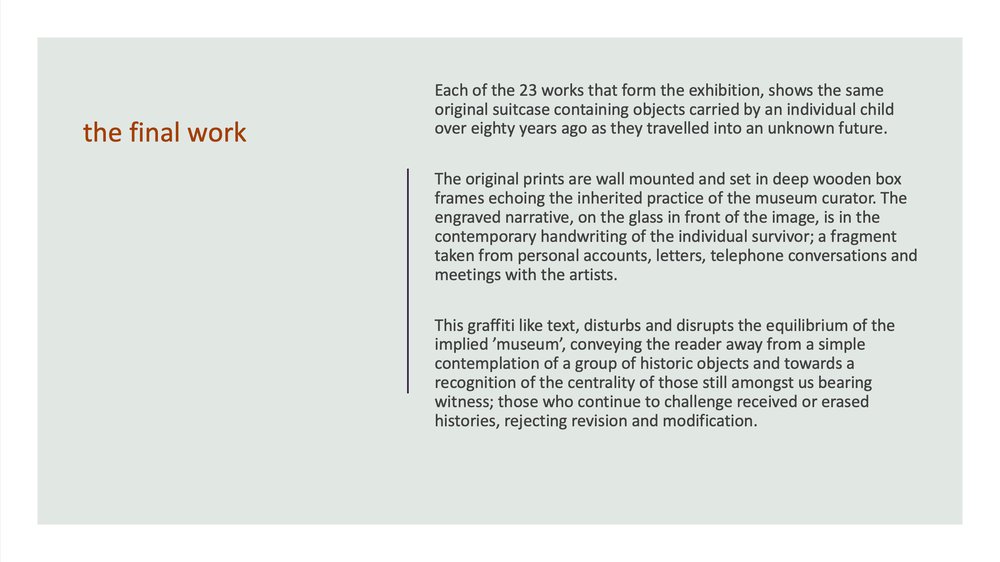

Each of the 22 prints that form the exhibition show an original suitcase containing objects carried by a child 80 years ago, as they travelled into an unknown future. The items belonging to each individual were placed within an original suitcase and photographed directly from above on a large format analogue camera, aiming to retain uniform perspective and actual scale in respect of the contents. In some instances the suitcase is quite full, in others it might contain only one photograph. This was entirely dependent upon the objects off ered to the project by the individual.

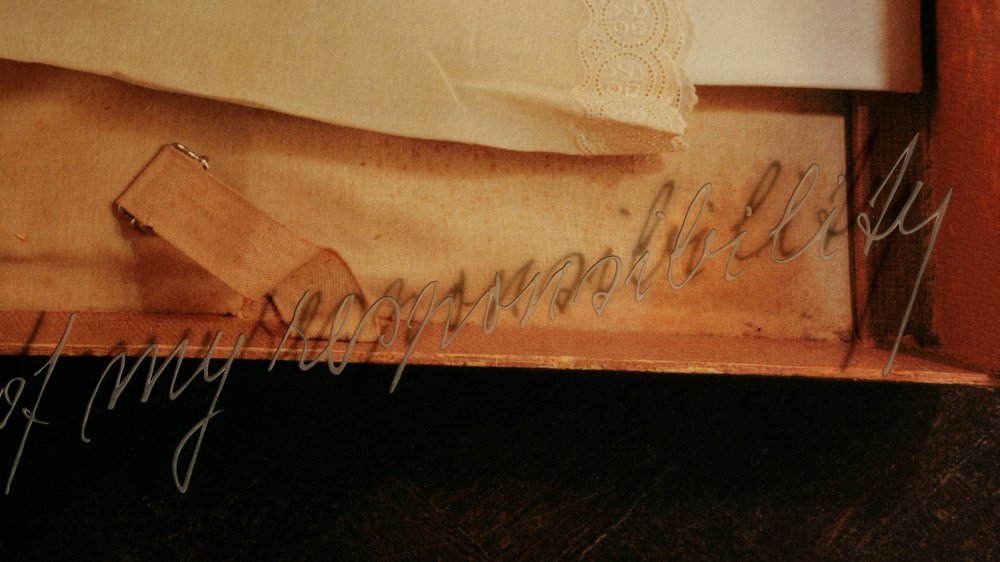

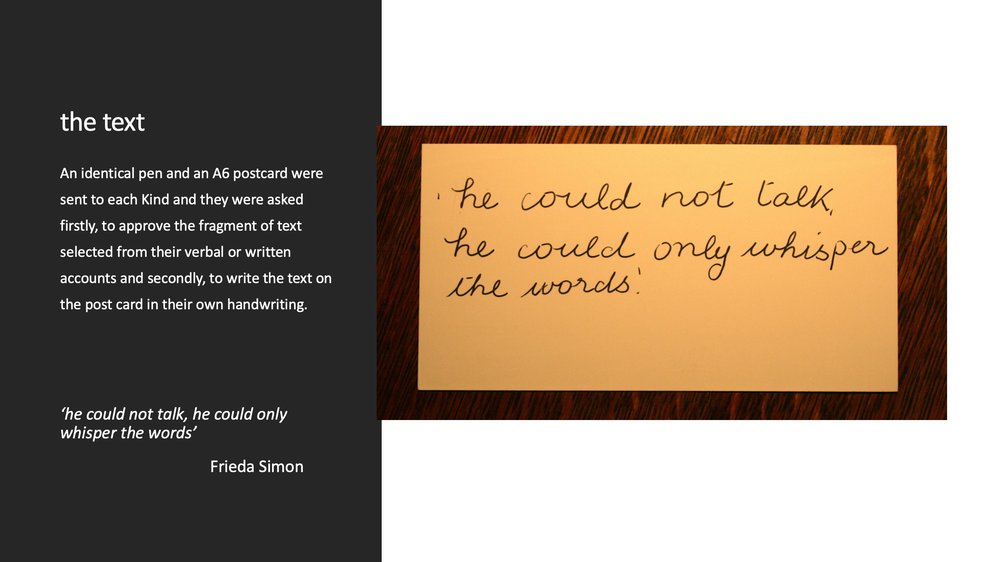

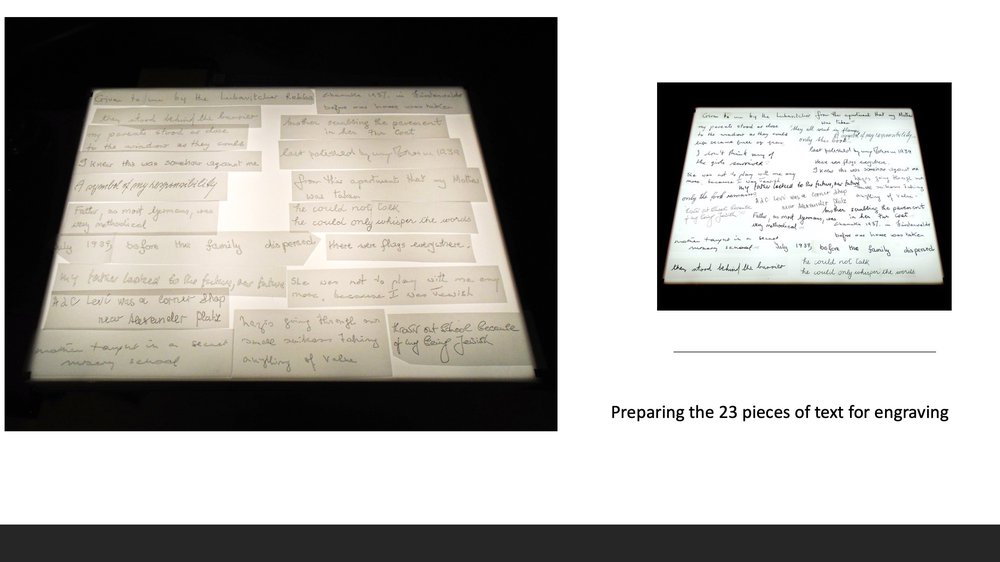

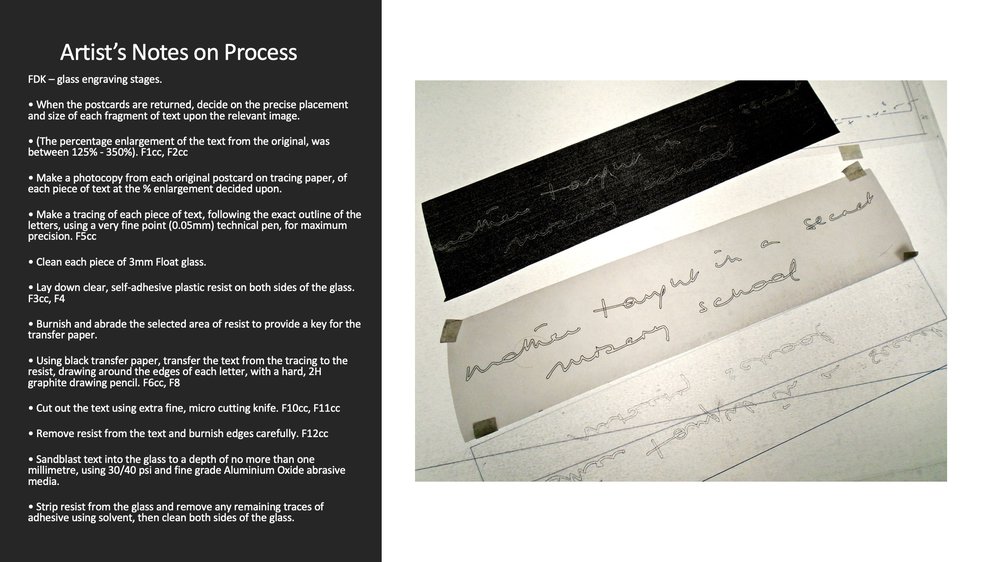

The title, FÜR DAS KIND is taken directly from a small group of objects contained within the suitcase belonging to Pauline Worner (nee Makowski), namely three children´s coat hangers printed respectively with the words, ‘Fürs Liebe Kind’ (For the darling child), ‘Dem Braven Kind’ (For the obedient child) and ‘Für das Kind’ (For the child). The engraved text, which is uniquely placed across and over the objects, is in the contemporary handwriting of the individual survivor, a fragment taken from personal accounts, letters, telephone conversations and meetings with the artists. The text gives rise visually to a subtle interaction of conflicting negative and positive emotions. Together with the shadows cast by changing ambient light, metaphors for memory emerge.

These personal treasures, assigned to each child at a critical point in their history, are signifi cant, not only in the context of a distinct religious background, but also as a major part of the individual‘ s sense of his or her own particular national heritage, in terms of its geography and cultural infl uence. In many instances the objects represent the last physical contact that a child had with either of their parents.

The artists wanted to provide the Kinder with a conduit for personal expression and so together they aspired to make a work that embodied a real and immediate connection to their experience and bore witness to key historical events that had indelibly shaped their lives.

The Rescuers

The Kindertransport was the rescue operation, a movement in which many organisations and individuals participated. It was unique that Jews, Quakers and Christians worked together to rescue primarily Jewish children. Many great people rose to the moment: Lord Baldwin, author of the famous appeal to British conscience, Rebecca Sieff , Sir Wyndham Deeds, Viscount Samuel, Rabbi Dr. Solomon Schonfeld, Sir Nicholas Winton who organised the Czech Kindertransports and the Quaker leaders Bertha Bracey and Jean Hoare and many others.

The Quakers

During the early years of Hitler‘s Third Reich, the Quakers established a reputation for their willingness to assist Jews or anyone else who sought refuge from Nazi Europe. The Quakers and the Jehovah Witnesses extended help to Jews in distress as a formal church policy. Soon after ‘Reichsprogromnacht / Kristallnacht’ in 1938, they lobbied and funded Jewish immigration from Germany and Austria. They also responded to the growing problem of caring for thousands of children and infants whose parents were shipped to detention or concentration camps by taking an active role in the Kindertransport. In a world torn by hate and war, the Society of Friends ministered to all people in pain — the friends were risking their lives by open opposition to Hitler‘s Reich.

The Christadelphians

The Christadelphians responded to the appeal to rescue children fleeing Nazi oppression by organising collections to fund the evacuation and finding homes within their community. They made regular trips to meet the young arrivals and to collect frightened and tearful children, some as young as three. The scene was such that‚ hardened London ‘Bobbies’ were moved to tears. Once the children had been collected, homes were found for them. Some hostels were established to look after teenage refugee boys during the war.

Sir Nicholas Winton (1909 – 2015)

Sir Nicholas Winton, then a 29-year-old clerk at the London Stock Exchange, visited Prague, Czechoslovakia, in late 1938. He spent only two weeks in Prague but was alarmed by the influx of refugees, endangered by the imminent Nazi invasion. He immediately recognized the advancing danger and courageously decided to make every effort to get the children outside the reach of Nazi power. He set up office at a dining room table in his hotel in Prague. Word got out of the ‚Englishman of Wenceslas Square‘ and parents flocked to the hotel to try to persuade him to put their children on the list, desperate to get them out before the Nazis invaded. ‚It seemed hopeless,‘ he said years later, ‘each group felt that they were the most urgent.‘ But Winton managed to set up the organisation for the Czech Kindertransport in Prague in early 1939 before he went back to London to handle all the necessary matters from Britain. For each child, he had to find a foster parent and a 50 pound guarantee, in those days a small fortune. He also had to raise money to help to pay for the transports. In nine months of campaigning, Sir Nicholas Winton managed to arrange for 669 children mainly Czechs, but also Austrians and Germans to get out on eight trains. One by one, English foster parents collected the refugee children and took them home, keeping them safe from the war and the genocide that was about to consume their families back home.

Rabbi Dr. Solomon Schonfeld (1912 – 1984)

Another remarkable rescuer was Rabbi Dr. Solomon Schonfeld who personally rescued thousands of Jews from the hands of the Nazi forces in Central and Eastern Europe during the years 1938-1945. A very charismatic and dedicated young man, he single-handedly brought over to England several thousand refugees and provided his ‘charges’ not only with safety, but also with homes, education and jobs. In the fall of 1938, following the ‘Reichsprogromnacht / Kristallnacht’, Julius Steinfeld, a communal leader in Austria, called Rabbi Dr. Schonfeld, pleading with him to assemble a children’s transport to England. Rabbi Dr. Schonfeld boarded a train to Vienna and helped organise a Kindertransport of close to 300 youngsters, providing the British government with his personal guarantee in order to secure their entry. Eventually he saved over four thousand children. Even before the Kindertransport, Rabbi Dr. Schonfeld brought 1,200 German Jewish communal workers and their families to England. He continued to lobby intensively throughout the war to fi nd temporary refuge whenever it was possible and managed to secure thousands of visas for people to escape. After the war he rushed to the liberated continent to serve the spiritual and physical needs of survivors and to evacuate them from war torn Europe.